by Erin Goss, Chapter member and Native Plant Initiative Coordinator for Shaw Nature Reserve

Autumn is a terrific time to explore nature: Deciduous tree and shrub leaves turn their spirited colors, late-blooming species like aster, goldenrod, and dittany mix purples and yellows and whites in a brilliant demonstration of color theory. Persimmon bark darkens and its leaves transform from green to yellow and orange with pink petioles. Its fruits dangle above like candy. Once ripened, they have a unique and nostalgic flavor beloved by humans and opossums. In late September, Horticulturalist Donald Frisch lead the Native Plant School class on a tour through the Whitmire Wildflower Garden and shared our patch of persimmons and what our team observes throughout the fall months.

Fall colors can be determined by the amount of daylight, temperatures, and moisture levels and occur across the plant kingdom. Ferns, perennials, annuals, shrubs, trees, grasses and sedges can all develop an autumnal hue. As it has been super dry, Donald noted that we are seeing early tree leaf drop before the leaves have a chance to turn, but many other species create a sort of flamboyant flora complete with varying leaf shades of blood red, bronze, butterscotch, copper, and purple. Fall bloomers like asters and goldenrod are essential to pollinators as they gather the remaining food before winter. These blooms pop with vibrancy – especially on those cloudy, moody days. Fertile fronds and wild indigos turn almost black. Just east of the Bascom House, Horticulturalist Joan Klingensmith designed and with the help of volunteers installed a garden that showcases the varying colors and textures of autumn. On our tour we observed this young garden, its delightful plant selection, and how bumblebees force their bodies into the closed flowers of the fall-blooming bottle gentian (Gentiana andrewsii) to access the delicious nectar inside.

We continued through the Wildflower Garden, stopping to admire the pink-blooming annual Spanish needles (Palafoxia callosa) (a shout out to Penny Holtzmann planting it as hedge!) and hypercolor-leaved littleflower alumroot (Heuchera parviflora) blooming in an ornate stone container. As we moved closer to the Home Gardening Shelter, Donald pointed out a hop tree (Ptela trifoliata) with egg sacs of the Two-marked leafhopper (Enchenopa binotata) – a treehopper species that has developed a reproductive rhythm with the hoptree’s sap flow.

He also pointed out blue waxweed’s (Cuphea viscosissima) sticky stems – a defense mechanism against insects, mistflower (Conoclinium coelestinum) in bloom, and purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) seed heads in varying states of forage. Finches particularly enjoy feasting on these seeds – in addition to Silphium spp., Rudbeckia spp., and Coreopsis spp. We also discussed the difference between American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) and the non-native beautyberry (Callicarpa japonica). American beautyberry has leaves that encircle the stems, its berry clusters are tight and snug against the nodes and it is upright in nature with larger leaves. The non-native beautyberry has leaves that are separate from the stem and smaller, its berries appear in loose clusters, and it tends more toward a fountain habit, a bit like a non-native spirea.

Keystone plants feature boldly in the fall, and we talked about Doug Tallamy’s Homegrown National Park and Grow Native’s Host with the Most Pack Cards. While white snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) is an aggressive spreader, it is also an important fall pollinator food source and Donald shared how horticulturalists in the Wildflower Garden let it bloom and then cut it back about a week post-bloom. While visiting the Frog Pond (a Wild Ones garden!), Donald shared that pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata) flowers from the bottom to the top and has many fauna associations, including a specialist bee, the longhorn short face bee. Dragonflies lay their eggs on the species, and frogs and lizards hide amongst the foliage.

On Thursday, October 17, Horticulturalist Emily Dunlap shed light on the more dangerous side of certain native plants. According to the Poison Control Center, while most poisonings are accidental – children and foragers are the most susceptible – some are intentional including a case of attempted murder using lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis) in Missouri earlier this year. While not a native species, lily of the valley shares a similar type of chemical compound (a cardiac glycoside) as our native milkweed, and during the class, Emily talked us through the complicated chemistry behind poisons and how some plants are safe and sometimes even medicinal in low amounts but toxic in larger amounts. Nature provides many, many toxins called phytotoxins and not all could be discussed in two hours, so Emily focused on four key chemical compounds, their characteristics, and native plant species associated. These phytotoxins provide plants with a competitive edge by protecting the plant from herbivory.

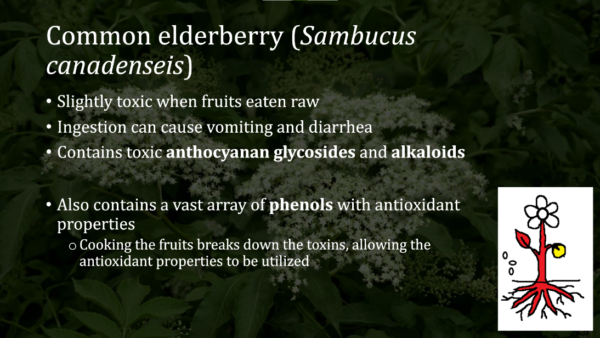

Phenols are the most abundant of these chemicals. A few examples of toxic phenols include the resins of the bark of the eastern leatherwood (Dirca palutris) and the entire plant of the American elderberry (Sambucus canadensis). Leatherwood resin can cause a minor skin irritation topically or act as a purgative if ingested. The entire plant in addition to the berries of the American elderberry is toxic and causes vomiting and diarrhea if eaten – though the toxin in its berries is neutralized through cooking or drying.

Alkaloids are found in over 27,000 different plants or approximately 10% of all plant species. Depending on the species and quantity they can either be toxic or therapeutic. Many of these are bitter-tasting and include wild indigos (Baptisia spp.) causing drowsiness, vomiting, blurred vision, and gastric pain. All parts of the Carolina moonseed (Cocculus carolinus) and common moonseed (Menispermum canadense) are fatal to humans if ingested but are wonderful food sources for birds. Other toxic alkaloidal plants include cupseed (Calycocarpum lyonii), wild four o’clocks (Mirabilis nyctaginea), and buffalo bur (Solanum rostratum).

Plants communicate with one another and other creatures through a collection of compounds called terpenes – these compounds help decide whether a plant wants to deter or entice. Both the tricorne larkspur (Delphium tricorne) and Carolina larkspur (Delphinium carolinana) can cause cardiac failure, convulsions and death if consumed. Flowering spurge (Euphorbia corrolata) – that lovely baby’s breath-like species has a milky latex that causes contact dermatitis on the skin and acts as a purgative if taken internally.

This is also true of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) though the young shoots and buds are delicious when cooked properly. The chemical compound behind this toxicity is glycoside. Members of the iris family including Iris cristata and Iris virginica have toxic rhizomes and roots. While dried roots of white baneberry (Actaea pachypoda) have historically been used to treat menstrual cramps, all parts of the plant are poisonous and can result in death.

We rounded out the class by discussing levels of toxicity and plants to very much stay away from including but not limited to poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) – never, ever burn it! followed by water hemlock (Cicuta maculata) and pokeweed (Phytolacca americana). Yes, you can eat pokeweed but take great care – it’s super toxic if not prepared properly!

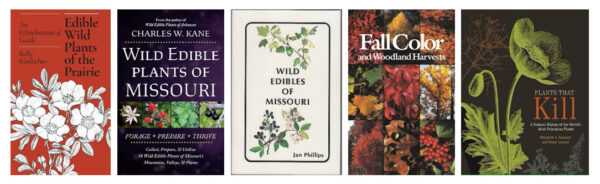

For more information, check out the Missouri Department of Conservation’s information page on fall colors, poisonous mushrooms, and edible plants. They also have a very helpful field guide that labels plants ‘poisonous’ and/or ‘edible’. University of Missouri’s Integrated Pest Management program has a useful blog post on Missouri poisonous plants. The Missouri Poison Center has a fantastic resource of native and non-native poisonous plants, and there are plenty of great guidebooks out there including Wild Edible Plants of Missouri, Plants that Kill, and Guide to Fall Color and Woodland Harvests.

Our two November classes are sold out, but please sign up for the waitlist! Horticulturalist Vivian Bouse will be discussing Landscape Reconstruction at Shaw Nature Reserve and Horticultural Manager Jen will share how to make Acorn Flour and Hickory Syrup at Shaw Nature Reserve You can join the waitlist by clicking the hyperlinks above or browse the full Missouri Botanical Gardens class catalogue. Our winter classes offerings will open soon and are typically held monthly on Thursdays at 1pm.

The generous support of St. Louis Wild Ones helps to make our Native Plant School classes happen, and we hope to see you there!