Editor’s note: You may not wish to read all of this, but just read the part about the area in which you live. Click map images for a larger version, or email me at brighoff@charter.net for copies of the map you can scale.

At Laclede’s Landing, the foot of Market Street, the belt of timber bordering the Mississippi River was narrower than usual. Prairie began at what is now Fifth Street (Broadway) and extended westward for up to eight miles to include most of today’s city. All this was not true grass prairie. In places it was distinctly bushy or brushy and in others there were scattered trees. In still others, grassy parks and groves of trees intermixed.

Some of Soulard’s plats clearly show that groves of trees (arboleda, in Spanish) occupied sinkhole depressions in an otherwise grassy karst plain. One French habitant testified that “the spot immediately where the town now stands was very heavily timbered, but back of the town it was generally prairie, with some timber growing, but where the timber did not grow it was entirely free from undergrowth, and the grass grew in great abundance everywhere, and of the best quality; but where the inhabitants used to cut their hay was where Judge Lucas now lives (Locust and 13th), and between his house and the cottonwood trees, it being all prairie” (Hunt’s Minutes 1825).

The French made direct use of the prairies behind their river border village. They apparently selected the most purely-grassy tracts for their common-fields and thus avoided the arduous labor of clearing timbered land. In fact, the French used “sur la prairie” to mean “on the common‑fields” (McDeLmott 1941). This usage of “prairie” for the cultivated fields may be the reason for Soulard’s regular usage of “prairie naturelle” for uncultivated prairie. The eufluuns (fenced pasture) were also laid out in the prairies, but these tracts were somewhat more wooded and served doubly as a fence and firewood supply.

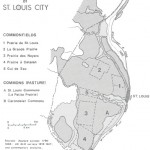

The French identified by name at least six major prairie districts within the present limits of St. Louis city (Peterson 1949). Immediately west of the village was the Prairie de St. Louis (a common‑field), bounded by Fourth (E), Jefferson (W), Market (S), and O’Fallon (N). This prairie, nearest the village, was the first utilized by the habitants. It was laid off in narrow strips stretching perpendicularly away from the river, each family having its own strip to cultivate. By 1811, not much of it was left in cultivation, and Brackenridge (1814) wrote that the “rest of the ground looks like the worn common…. the grass kept down and short, and the loose soil in several places cut open into gaping ravines.” North of the road to St. Charles (about Martin Luther King Boulevard) the prairie was known as Prairie de la Grange and extended north to Palm Street.

To the south of the wooded valley of La Petite Riviere (later called Mill Creek and now the low area occupied by the railroads and Union Station) lay La Petite Prairie which was part of the large St. Louis Commons (pasture). The commons began at Chouteau Avenue and extended south to Osceola Street or Cleveland High School. From the crest of the river slopes it extended westward to Grand Boulevard. This open land was described as having numerous springs with scattering trees and groves, making it more suitable to pasture than to cultivated land. It was a major source of firewood for the habitants. A true, grassy prairie tract, specifically La Petite Prairie, was between Russell Boulevard and Arsenal Street. Peoria Indians once encamped in this tract, whence a second name for the prairie, Prairie du Village Sauvage.

La Grande Prairie lay in the north central part of St. Louis city, bounded approximately by Grand (1), Newstead (W), Easton (S), and Carter (1), and including Fairground Park. La Grande Prairie was the largest true prairie in the city. Like other common-fields, it was laid off in long, narrow lots for the families of the village.

In the south-central part of today’s city lay the Prairie des Noyers (noyer = walnut) bounded by Park (N), Chippewa (S), Grand (E), and Kingshighway (W). Tower Grove Park and the Missouri Botanical Garden are within this prairie, which was also subdivided into common-field lots.

To the south of the Prairie des Noyers and behind the village of Carondelet was the Prairie a Catalan or Catalan’s Prairie, named after an early French settler, and which served as the common-field for Carondelet. The commonfield was bounded by Compton (E), Meramec (N), Morganford (W), and Loughborough (S), and includes Carondelet Park. The village of Carondelet, like St. Louis, occupied a narrow belt of river border timber, centered on Haven Street. The Carondelet Commons (pasture) lay south of the commonfields and extended well south of the River des Peres to just beyond Forder Road. The Carondelet Commons, in contrast to the St. Louis Commons, was more thoroughly wooded and never described as prairie.

La Prairie du Cul de Sac, smallest and most wooded of the prairies functioning as commonfields, lay in the upper parts of the valley of La Petite Riviere, or immediately east of Forest Park. The common-field laid out in this open land was bounded by Chouteau (S), Forest Park Parkway (N), Vandeventer (E), and Euclid (W).

From La Grande Prairie in the north to the Prairie a Catalan in the south, lay an unbroken, eight‑mile stretch of prairie land to serve as common-fields and pasture for the French. Wood from the prairie could be used for fuel and fencing, but most fencing and all large timbers for construction had to be brought from the American Bottoms in Illinois or from up the Missouri River. Peterson (1949) suggests that the growing scarcity of fencing materials seemed to have been a contributing cause of the collapse of the common-field system about 1798. Stoddard (1812) wrote that the extensive prairie back of St. Louis would probably remain uncultivated “from the want of timber to fence it.” The St. Louis prairies, everyone agreed, made superb pastures for cattle and horses. Stoddard further commented that “no hay is necessary, except for such cows and horses as are stabled, and plenty of this is always to be obtained in the proper season from the prairies.”

The tract in the southwest part of St. Louis city between Chippewa (N), Kingshighway (E), Gravois (S), and the River des Peres (W) was prominently labeled by Soulard as a “grande prairie naturelle,” privately claimed, but unoccupied and unused during the Spanish days. In the very northern parts of today’s city, the land survey lines now represented by Florissant Avenue and Riverview Boulevard were described as late 1817 as “prairie, with no timber.”

At the turn of the nineteenth century there was more bottomland along the Mississippi River north of downtown St. Louis than there is today. A large part of this flood‑plain was prairie (prairie basse). Where Maline Creek and Gingras Creek came out of the bluffs (cotes), they turned to flow along the base of the bluffs for over four miles before joining the Mississippi River. Here the bottoms were more than a mile wide and prairie naturelle occupied half or more of the width. On the Dufossat map of 1767 (Garraghan 1928) this bottom prairie is named Prairie de la Joie, but this name does not seem to appear in any other source. A French road (chemin gui passe au pied des cotes), now Broadway, took advantage of this longitudinal prairie bottom, in places as far north as the Missouri River.

The French named two other prairies in present St. Louis city, but I have not definitively located them. Prairie of the White Ox was “several miles north” of the village, and Prairie of the Three Bulls is known only by name.

Two other French villages, Florissant and Village a Robert or Marais des Liards (Bridgeton) were in St. Louis county by 1800. Both were laid out in prairies, and, like the village of St. Louis, both used the prairies for common-fields and commons.

Florissant was in the middle of “one of the must fertile and valuable prairies in the country” (Stoddard 1812). It reportedly got its name, Fleurissant, “because we can well imagine the wild flowers then bloomed luxuriantly in the open prairie, and deeply impressed by their beauty even the rude hunters and trappers who first beheld the virgin land” (Houck 1908). An earlier name (1763) for the prairie at Florissant was Prairie les Biches (biche = elk or roebuck), after Riviere aux Biches, an early name for Coldwater Creek which flowed through the broad prairie lands of north St. Louis County. Almost coincident with the saucer‑shaped Florissant Basin, the Florissant prairie was the purest grass prairie described in early French and American accounts of St. Louis county. It extended north to the Missouri River bluffs near Fort Bellefontaine and southeast along Halls Ferry Road into the present city of St. Louis and merged with La Grande Prairie.

Village a Robert occupied a site just west of Lambert Airport. Its commons (pasture) and common-fields merged with those of the Florissant prairie. On the south side of the Village a Robert, in present St. Ann between I‑70 and St. Charles Rock Road, lay the Marais des Liards (cottonwood swamp). While cottonwoods grew along the sluggish creek, prairie grass covered most of this wet tract, and it was very early claimed for rich pasture.

An unnamed but distinct prairie spread over the uplands around Spanish Lake in extreme northeastern St. Louis County, overlooking the junction of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. This prairie was variously described in parts as “prairie naturelle” and “good prairie land” and in other parts as “prairie et bois clair; “no timber,” and “rich barren land.”

Between this prairie and the Florissant prairie was land that clearly had been prairie earlier, because by the end of the eighteenth century it was described by words which indicate forest invasion: “oak bushes, no timber”; “scattering black jack”; “scattering black jack and thickets”; “thin scattering black jack.” The present suburb of Black Jack is in this tract, its name quite accurately reflecting its early environment. Stoddard (1812) commented that the Florissant prairie was twelve miles long, extending from Marais des Liards to the long point famed by the junction of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. If that was so, then the black jack scrub woods around Black Jack represent one of the first documented conversions of prairie to woods in Missouri.

West central St. Louis county, including University City, Richmond Heights, Clayton, Brentwood, Ladue, Olivette, Overland, Maryland Heights, Creve Coeur, and intervening places, was a mosaic of prairie, brush, woods, and timber. Boundaries between these vegetation types were not sharp, and consequently the prairie boundaries shown on the map are better interpreted as transitions. Soulard made fewer surveys in this area, and the vegetation may have changed by the time of the General Land Office surveys in 1817.

Although the pattern is complex, one generalization is noteworthy. Prairies occupied broad valley bottoms and slopes, while blackjack, and less-commonly other oaks, occupied the ridges. This arrangement is the reverse of the usual prairie‑timber topographic relationship in Missouri. Deer Creek Valley, from Brentwood Boulevard west to I‑244 (ed. I-270), was prairie. The survey lines now represented by Litzinger Road in Ladue and by Ladue Road in Creve Coeur were both described as priarie. On the other hand, the high ridge from Clayton and Price Roads in Ladue (St. Louis Country Club) northwestward to the junction of Lindbergh Boulevard and Olive Street Road and then westward on Olive Street Road was all in blackjack, black oak, and hickory timber. Similarly, the ridges around Maryland Heights were in blackjack, while the valley swales were in prairie grass.

The land between the River des Peres and the Meramec River (“South County” today) contained much less prairie land. The tract of upland prairie (prairie haute) lay on the high ground in Affton bounded roughly by Gravois Road (S), Mackenzie Road (E), Heege Road (N), and Laclede Station Road (W). In the valley bottom of Gravois Creek prairie was described in two long stretches and in this respect the valley resembled many “prairie hollows” of the Ozarks. One of these prairie bottoms is now traversed by Grant Road in Grant’s Farm.

The coarse‑textured alluvial bottoms of the Missouri River in St. Louis county supported no prairies, in striking contrast to the numerous bottom prairies along the Mississippi River. Travelers noted this difference. Flint (1832) wrote that “prairies are scarcely seen on the banks of the (Missouri River) within the distance of the first four hundred miles of its course.”

Prairies covered much of St. Louis city and county when the French settlers arrived, and they persisted well into the nineteenth century. The St. Louis prairies took different forms: dry upland grassland, wet upland meadows, grassland with scattering trees, grassland with brush, grassy parks and groves of trees, and bottom prairies along the Mississippi and other streams.

These prairies functioned integrally in the life of the French villagers and early Anglo‑Americans. They were the sites of the first cultivated fields, and they served as natural grass pastures and hayfields, the source of fire and fence wood, and the place to hunt game and collect strawberries and other fruits. Early roads were located in prairies wherever possible.

While the origin of the prairies in their different forms is not the purpose of this paper, it is worth noting that the French and early travelers considered fire responsible for both the creation and maintenance of prairies. Other ideas have since been suggested, however, such as the agricultural fields necessary to support a sedentary population of 25,000 or more in the Cahokia Indian complex in the adjacent American Bottoms in Illinois.

With expanding settlements and farming in the nineteenth century, the prairies began to disappear. By the summer of 1836 Flagg (1838) saw a landscape west of the city “clothed in a dense forest of blackjack oak, interspersed with thickets of the wild‑plum, the crab‑apple, and the hazel. Thirty years ago, and this broad plain was a treeless, shrubless waste, without a solitary farmhouse to break the monotony. But the annual fires were stopped; a young forest sprang into existence and delightful villas and county seats are now gleaming from the dark foliage in all directions.”

In 1843 a government report (Nicollet 1843) declared the “beautiful prairie” of Laclede’s time was “already giving the promise of a renewed luxuriant vegetation, in consequence of the dispersion of the larger animals of chase, and the annual fires kept out of the country, since the arrival of the whites on the Illinois side. At present, this new growth is again doomed to destruction; but the process is carried on with more discernment, and for a more praiseworthy object: it is for the extension of the city, for the erection of manufactories; for clearing arable lands‑‑in short, for all the purposes of a progressive state of civilization.”

Still later, the Soil Survey of St. Louis County (Krusekopf and Pratapas 1923) reported a sparse tree growth had established itself over land that was prairie at the time of the first settlements and that the only “remaining prairies are found in the Florissant Basin, where an abundant moisture supply has favored a heavy grass vegetation.”

Now even the Florissant Basin is nearing full urbanization. The once extensive prairies of St. Louis city and county, eighty-thousand acres of them, have vanished.

Note: this article was re-printed from the Missouri Prairie Journal, a publication of the Missouri Prairie Foundation.

Immediately west of the village was the Prairie de St. Louis (a common‑field), bounded by Fourth (E), Jefferson (W), Market (S), and O’Fallon (N). There was another prairie common field that began on Jefferson and ran west to Vandeventer.